The Nuclear German program was led by several groups of scientists including Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg team, but never achieved its goals. Fortunately, after five years of research, the program never succeeded in achieving a chain reaction.

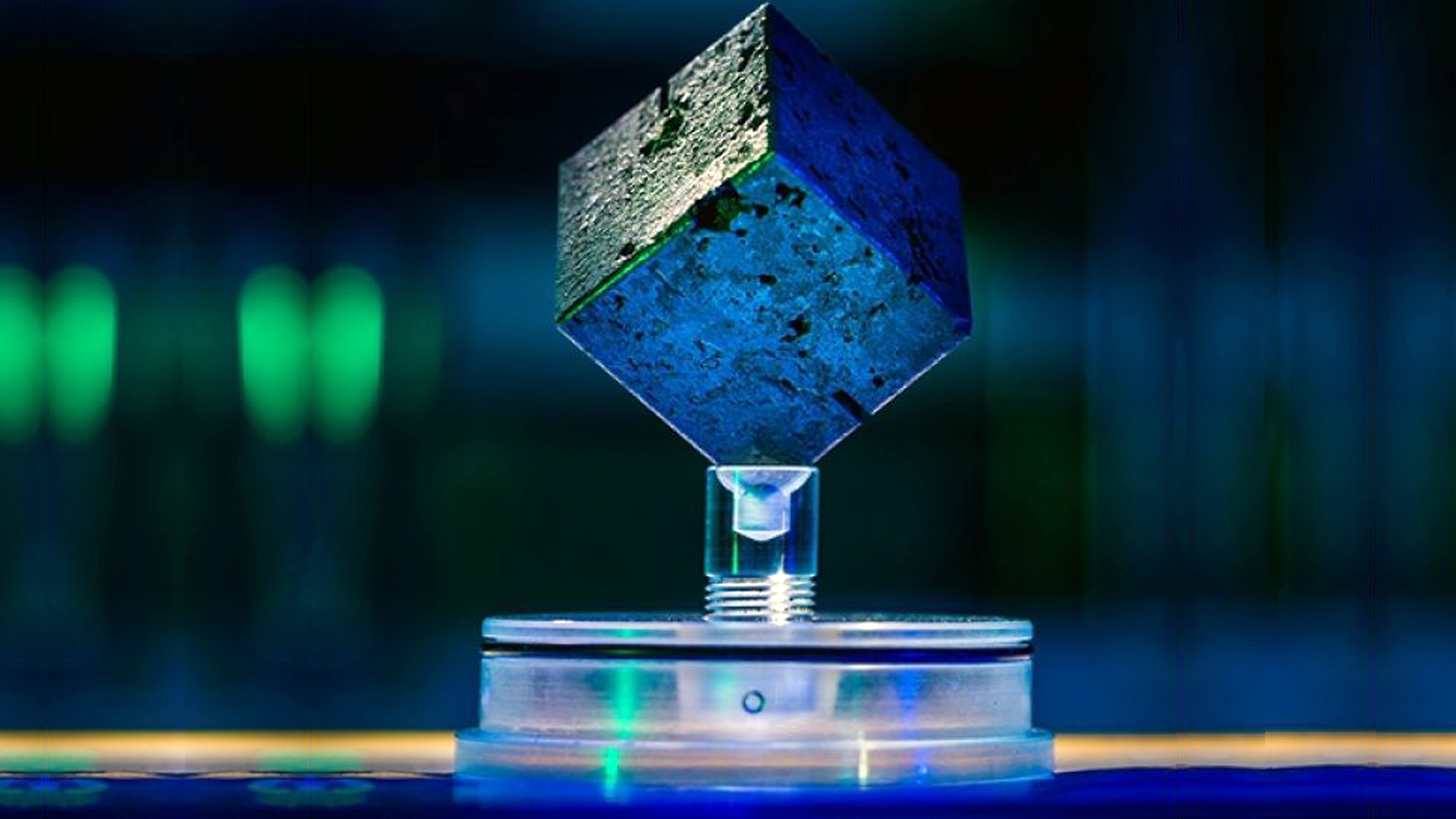

Part of its failure was due to the rivalry between the different groups of researchers to obtain the raw materials with which to build their corresponding experimental reactors. Those reactors were very different from the conventional experimental piles formed by a stack of blocks of uranium metal interspersed with other blocks of graphite that act as a moderator. They were formed by cubes of 5 cm on each side and weighing approximately two and a half kilograms that hung from cables and were immersed in a tank of heavy water.

Today they are popularly known as “Heisenberg cubes”, but there were actually two groups of researchers who used this technique: Diebner’s team and Heisenberg’s team. The cubes of both projects, of which it is believed that there must have been about 1200 units, have some differentiating characteristics related to the origin of the uranium used in their manufacture and the coating used to prevent corrosion.

At the end of World War II, the Allied army dismantled the Heisenberg reactor (B-VIII) located in the city of Heigerloch and more than 600 cubes were sent to the United States where they were used in the Manhattan project, although some belong to institutions or collectors. The final destination of rest of the cubes, including Diebner’s, it is not known.

Last August researchers from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) presented at an American Chemical Society conference the development of a technique called Uranium Radiochronometry. This technique, considered to be the nuclear version of the technique geologists use to determine the age of samples based on radioactive isotope content, will allow the pedigree of several cubes belonging to PNNL and the University of Maryland to be identified.

The cubes, which are routinely used to train border security personnel in the detection of nuclear material, represent a great opportunity to test this science before applying it to actual nuclear forensics techniques. Future practical applications of these techniques are still to come, but for the time being they will shed light on the circumstances of one of the earliest chapters in nuclear history, the failed German research program of World War II.